Salad Baby

When we’d put off her first bath embarrassingly long enough, I finally placed the wailing newborn in my parents’ oversized stainless steel salad bowl, on their deck, in the fishhook of August heat. I counted to ten: a newborn bath should take about as long as roasting a marshmallow, or dipping cantaloupe in chocolate fondue.

“Delay” is the recommendation for the bath in the hospital. Always late to the party, we “delayed” almost an entire moon cycle, until Mercury was in bath-e-grade. During a particularly ragged 3AM feed, I paced in the thinning dark, nursing her while walking to stay awake, when suddenly, the vanishing stars became didactic. Orion lashed my consciousness with his scar-crossed belt: BATHE HER! (Ya know-it-all-male-bastard, how about you get your ass down here and try?). The Big Dipper dangled like Damocles sword, an accusatory oversized diaper pail. Aren’t you going to at least DIP her in something water-like? I was a trash parent, wasn’t I? I could handle this.

With the baby draped over my shoulder, I hunted through the cabinets for something usable. It seemed safe enough: stainless steel is gleamingly nontoxic. You can’t really slip or drown in a salad bowl, unless you try very very very hard, something newborns are not known for. For me, a diehard vegetable-aholic, the bowl held congenial associations, if you find Earth Bound mixed spring lettuces and cucumber comforting.

Once the sun rose and I “filled” the bowl, she just barely fit in it, the water displaced along the line of her belly, and the WTF look spreading across her face like a second, way less satisfying dawn. Try new things with infants in the morning, right? If you can call placing someone in dishware with an inch of water in it bathing, it was successful, ish. I couldn’t tell if I was resourceful or completely useless.

Read the rest on my substack, MOTHERINK. (Become a free or paid subscriber!). See you there.

To The A-Hole In The Pool Lane, Before My Cesarean

When I was 8 months pregnant and my rogue pinky toe was broken, a lane-hogging swimmer, an older man with a bushy mustache and an algae bloom of chest hair, tapped my shoulder blade percussively as I clung to the pool wall after completing a lap. "Maybe you should go in the slow lane instead?" He suggested, huffing his water droplets all over me.

"Or maybe you should go in the asshole lane?" I replied, as if trying out the next general theory of matter. In it, people like him would show unprecedented atomic density. I held up fake binoculars and sought bluer pastures across the plastic separators.

His black fins sent torrents of water sloshing over the perimeter of the pool, making it impossible for someone to swim even a near distance behind him. Would you swim in the wake of Cuisinart blades? The asshole always needs to make a splash.

He blinked, pushed off the wall, and began his next flailing lap, propulsed by his self-righteousness, which was as pronounced and visible as an Achilles tendon. As a slightly anemic and very pregnant person, it took me as long to catch my breath as it had to swim the 25 yards. Maybe he was right.

My overstretched bikini bottom (but do you honestly buy another one this late in pregnancy? My theory is always: no) dragged behind me when I dove under the water, and the refracted light was a coronation on no one, nothing. I loved that moment before I ran out of breath, which would go on to characterize 98 percent of my birth.

In truth: the asshole lane is open longer than all of the others and is always crowded, because every row is theirs and (your) time is nothing (and not in the liberating way) to them. They are not hard to spot, like a hammerhead shark in a jelly jar. Most are ableist, sexist, and notably horrible at the breaststroke. The dividing line painted down the middle of the pool floor-- which stands for basic principles of sharing & caring -- is irrelevant. Why notice what doesn’t apply to you?

I’ve heard that same tone of surety when (some!) OB's in the MIC speak to clients, or to me. Pretending to be a lifeguard, their suggestions are too often demeaning threats. In order not to drown, we might contort around their ego’s deliberately exaggerated and space-hogging crawl. Or we accept the ladder they are holding out, despite not having signed up to be saved.

My baby hung from my belly in the water, the weight lifted off my back and legs, and my uterus felt, briefly, like it could evade the ravages of gravity. I tried to focus on the beautiful things behind and ahead and the sharp peck of chlorine in my nose. I imagined all the children who had peed here, their low-grade biohazard (parenting, you realize pee is the least worrisome bodily fluid) dissipated by the paradox of harsh chemicals that keep us, the public, somehow healthy enough.

It's a terrible thought that you might not make it to the end of the lane, to the touching of the wall that weeps differently, to your recovery breaths. That you might not recover. It's a terrible thought that, confident you could cut through the sensations, you might just dematerialize, decompose, drift apart like spit fronds in a rushing river.

But assholes energize me. No sooner had he made his next pivot than I lapped him. Mild Anemia be damned. My baby, whoever they were, should know how to handle assholes too. And definitely never to be one. As he crashed towards me, panting, more donkey than dolphin, I tapped his shoulder blade (like unto like) before he completed his final stroke. Should I pee right there, to highlight my announcement? What could he do? The chlorine would not protect his dignity.

"I'm 8 months pregnant, asshole," I reported. "How fast would you swim if you were carrying three chain-saws?” I pushed off with the non-broken foot, and began a languorous doggy paddle just ahead of him, moving slowly, awkwardly and flaccidly enough that each palm, on its downstroke, gave effleurage to the baby's uterine domain. He spluttered at me. I was a Noh performance, on quaaludes. He could wait.

Originally, I planned to give birth at home in an inflated pool, perfect blue, the plastic elephant in the room. Instead, half-submerged in the lukewarm water, I felt like someone was driving a stake up into my pelvis. “ASSHOLE!!!!!” I might have yelled at God, who quietly made more room for me to be me in our shared aqueduct.

At the darkest midnight of my labor, where I expected to experience a deep surrender to the tide, everything felt crass, debilitated, sharp. The wrong direction, the wrong texture. But wasn’t I in the optimal medium for the smooth, fleshy baby to wrangle its way out, traveling from original waters to expressly recruited tap waters? Wasn’t my body sort of made for this?

In those brutal hours begging for mercy in the birth pool, I cried: the fucking waterbirth website lied! If this is reduced pain, what is pain? If this is maternal satisfaction, what is misery? The water trembled, my husband gave counterpressure like a boulder gives to the earth, but the baby–yield and breathe and holler and whistle-blow as we might– would not change lanes. There was no other lane but the one we were traveling.

Later I knew: it was too slow. I was too slow, then too fast, too fast. Later I understood: the light was coming through anyway, dazzling, dappling, broken, salvatory, an invisible coronation. The baby was not supposed to come out in that context. The asshole was not supposed to make way for me, nor was his wake supposed to christen me as anything lesser than a powerful being encasing a powerful being, albeit in an underwhelming nylon bikini. Sometimes, the pace is not up to us. Sometimes, our most heroic gesture is to swim in the other direction, displacing the space our old self was suspended in.

***

AFTERWORD

**Because I’m a labor doula, I want to differentiate my experience from the data: the waterbirth website didn’t lie at all. There are many deeply positive effects of laboring and birthing in water. However, we can feel betrayed in our birth when our experiences differ radically from what we hoped or expected. I would recommend waterbirth to someone who is interested and for whom that is a safe option. My first baby experienced a cord prolapse, a very rare medical emergency, and was born (thankfully safely) by emergency cesarean after a homebirth transfer.

She just needs a flower

My 4 y/o completely lost her s*&t on the cold-ass street, jellyfishing and refusing to not refuse to walk. We were about to miss pickup for my 7 y/o from his DOE school bus, which waits for no one, and I was not feeling her not feeling it– like, at all.

But then this shopkeeper stuck his head out of the flower shop, in front of which her fit was unfolding with impressively vast limbic inflection for someone only on her 1200th day of life or so. He asked, “Does she need a flower?”

The surprise cut her off from her operatic emotional outburst. Well of-fahking course she does! THAT WAS THE PROBLEM ALL ALONG! NOT ENOUGH FLORAL TONES AROUND HERE! She stared at him, too much of a yes to say yes. “Be right back!” He reassured me. My frustration was carbonated. No prob! Timely! He popped back into his expensive-as-all-high-hell flower shop. The door jangled. I could not afford these minutes, but I could not afford to not have the flower happen.

We stared. Sure enough, jangle-jangle, he came back out with a fat-petaled purple tulip and peach-pink rose, dewdrops still in formation, and handed them to her with a robust smile, and that salesman inner knowing that I would buy overpriced plants from him for the rest of my days. “Hope it works!” he winked at me.

She took them, awe creeping across her face: “My favorite clolors!”[sic]- and she sheltered them in her jacket all the way to the bus, fit interrupted, fit forgotten. “Look!” she whispered to the flowers, or to me, or to everyone. The wind *clolored* in her face a deep wounded red, but the flowers were and remained perfectly intact and undisturbed.

I could milk this experience for analogies forever, but a few things stick out:

When the emotions are too big to bear, give someone a flower.

When the emotions are too big to bear, a little act of beauty can help a whole lot.

He totally didn’t need to give her the flower.

If you want people to buy shit from you, help them through a very tough moment.

It was March and he had a sign on his shop door that mother’s day was May 14th. Plan ahead!

#parenting #emotions #beauty #protips #tantrums

My Regards to the Monitor

Hours after I had the baby, Dr. F told the monitor near my face that it was very sick and would need a blood transfusion. I felt bad for the monitor, such a rough start to the day– it was only 5:30AM.

I could smell life: some people were having toasted onion bagels with cream cheese falling out the sides or hospital hazelnut Keurig coffee which burned their tongues. Other people were being transfused. The monitor had worked hard all night in emergency childbirth. For what?

Minutes later, when the monitor didn’t respond or react to his announcement, I realized he meant me, I was very sick, he just hadn’t thought to look down 45 degrees to where my face was.

I didn’t think I could get up from the hospital bed anyway. The fact that the bed could be completely broken down was the only reason I had confidence I’d ever not be in it. My sacrum was one with the thin padding they referred to as “mattress.” I tried to explain this to Dr. F but it came out like this: “OK.”

I wasn’t on drugs, exactly. I mean drugs were in me– morphine, and rights to tap the pump further- but I felt nothing like a person on them. It was like the drugs were scoping out my vascular system, an apartment they were considering renting, but it turned out the infrastructure was kind of shitty, and there were exposed wires in the kitchen– so, no.

Dr. F left to go make other statements other places, and some family who were around held my hands and tried to show me pictures of the newborn in his little bin, and that was helpful, because in theory there was a beautiful tiny fighter of a person who had come out of me and he was in a different room, that was all.

I didn’t actually understand what transfusion meant or why I was suddenly sick except that emergency surgery is always a roll of the dice, so when the doctor eventually came back, I asked why and how and what, and he nodded at the monitor. I guess his procedure was not the rushing and yelling kind of transfusion that I remembered from the show ER. But oh how I wished George Clooney was here, because he would definitely take my questions, or blink compassionately at me with his lifesaving and only-slight-egotistical big eyes.

Being inside the ambulance hearing the siren is very different than being outside. On the streets, your adrenaline and empathy stirs, even raising hairs, and you are fleetingly aware of some of the most profound human misfortunes, and maybe cover your ears. Inside the ambulance, you are the peristaltic movement of misfortune. You are misfortune’s etiology. You may have had your last toasted bagel, and you reckon with that in a metal box traveling at the highest permissible speed.

When Dr. F came back back for the third time, the monitor had gone to sleep. In my memory, he apologized. He didn’t want to wake up the monitor. It’s against hospital policies for postpartum people to get satisfying naps, but monitors, no problem. They need a little recovery time. But also: I wasn’t sick. It was a mistake. They had retaken my iron. My iron levels were fine. Lab error. Oops. Happens sometime. My blood was red. The sky was blue. The sheet was white. And the baby was alive, and I was going to see him, in his little incubator box, his little eyes programmed to find my eyes, and stay.

**

Still making sense of your birth? Want to get it all out, the way you remember it? The gorgeous and the difficult? In your “Tell Your Birth Story” session, we do just that, and you receive a complete narrative record as a keepsake. Flexible scheduling link is sent with your purchase receipt.

Lil Placenta

My four year-old daughter held out the bright red slime she’d pilfered from my son’s Valentine’s Day goodie bag. “Look, it’s a placenta!”

My four year-old daughter held out the bright red slime she’d pilfered from my son’s Valentine’s Day goodie bag. “Look, it’s a placenta!”

Well, no, it was actually just slime. The placenta is more formidable. Heavier. A different kind of party favor. But at our house, we don’t use cute pseudonyms for things bodies do and are. Biology comes to the dinner table, and knows the fork from the spoon from the sex-iled knife.

One time, I transported my labor client’s freshly delivered placenta in a soft cooler bag, on ice, on the bus. Another rider shoved past me, pushing the cooler out of my hand.

“CAREFUL WITH MY PLACENTA,” I whisper-shouted (“my” in the loose sense). Because it’s New York City, the commuter– a guy– did not blink.

All the way uptown on the bus, I felt like I had a secret in the silver insulated bag, held by its too-small plastic handles– and I kind of did. But only as much of a secret as any of us have who cart around a heart all day. A brain. A wedge of sadness they just can’t swallow.

Now my daughter twirled through the apartment with the beginnings of a reproductive agenda, the red slime in a repurposed take-out container, like a misplaced sacrament. There used to be Lashevet’s babaganoush in there. From Eggplant to egg sustainer.

Generally, I don’t really do take out. It’s Home kitchen all the way, and green vegetable panacea. I’m very aware that these cheap plastic containers easily degrade. Claw their way into your food– your organs– your (in the loose sense) placenta. Yet manufacturers make these little containers the perfect size for future storage. A convenience slowly poisoning the planet, for the sake of transportable hummus.

When you order for 6+ hungry people (blended family, many appetites) the containers are fruitful and multiply. Once emptied, you can nest them in a planet-defying tower, like vertebrae without a body to hold up. But children can do anything with anything.

The four year old admired the shape-shifting organ of which she was now the only Keeper.

Little Rules, my 7 year-old, insisted, “That’s NOT a placenta, you can’t just keep calling it one!” His brain works like a deli meat slicer. “That’s like saying an elephant is a speck of dust.”

Little Pleasure refuted his argument by shaking her head until she fell over.

Little Rules felt the power of his first analogy and immediately upgraded, “That’s like calling a mouse a LION. It’s not a thing just because YOU SAID IT IS.”

Oh? Isn’t that what writers do?

Little Pleasure was not dissuaded, “It’s a placenta from mommy’s body. And you can’t touch it!”

Yes, I’d lost two of those glorious, multi-talented organs that support and maintain incipient life. The shared, indisputable arbiters of survival. Both to the hospital pathology bin. I didn’t touch either. One I never even viewed.

More adults have seen the neon slime elementary school kids love to fling and fake-sneeze with than have seen a placenta. Why?

Kids have more experience with slime than awareness of placentas. Why?

Most grown people don’t understand what’s so important about the placenta, either. You know how you only understand the architecture and function of a knee cap when something goes wrong with yours?

I have questions. Like:

Can’t we do better?

Can we remember that, once, we each needed a placenta? Like, wholly? And like, be a little kinder now, because we all still need something?

That we are made of layers, complicated layers? Some a tad slimy?

Can we consider that we’re temporary take-out containers, too. The biology that holds the transient mystery?

Also: did you know more than 900 species of slime mold occur globally, an indomitable force, isogamous organisms? Me neither. Little Rules told me that, with the gloppy red substance-- definitely not-placenta but still subjectively magical-- wobbling in his lap.

***

Not sure what parts of your birth or the aftermath you want to talk about? Not sure what parts matter to you? Already missing your placenta, or forgetting what it meant to create and birth a human?

Come tell your birth story in a 1:1 private session with me, fully supported, in organic detail, and create a meaningful narrative record for yourself and your family. www.tellyourbirthstory.com

The Most Expensive Sound In the World

In the middle of the season I transitioned into stepmother, the retired cop sat my students down in the conference room where trillion dollar deals are brokered, as they squirmed in their suits, heading into their second semester of senior year and then one wild summer before college. He played the sound of a baby crying for a full minute.

In the middle of the season I transitioned into stepmother, the retired cop sat my students down in the conference room where trillion dollar deals are brokered, as they squirmed in their suits, heading into their second semester of senior year and then one wild summer before college. He played the sound of a baby crying for a full minute.

“You know what that is?”

My students looked at each other, laughing nervously.

“C’mon, seriously. I am asking you,” the cop smiled tightly. “You know what that sound is?” The cry cut through the bank offices where the fellowship was held, cracking inoperable windows, and setting the oversized Warhols askew. The bathroom orchids averted their stamens.

Teen 1 raised his hand. “Is this a trick question?”

Cop, “Do I look like I am playing around?” He stuck his thumbs in his holster, for effect, where an unloaded gun hung, of course for effect. A cop had to look cop! “Well?” My ovaries covered their eyes.

Teen 1: “No.”

Cop: “You are telling me that you don't know that sound? Brother, for real?”

Louder and louder grew the newborn’s siren.

Then, Quiet. The jittery feeling of being tested. Who likes to falter in the face of the obvious? Definitely not a room full of jocular guys.

Teen 2 stepped in, he could always smell tautology coming from down the hall: “It’s a baby crying, yo!”

Cop: “Nope.”

Teen 1’s collarbones hiked up, indignant: “It is!” He stood up. “It IS!”

Cop: “No, it is not. That, fellows, is the most expensive sound in the world.”

You could have heard an embryo fart.

I was, at that very moment, paying for Saturday childcare for my almost stepkids. 20, 40, 60, 80, 100. 120. Late train, 140. Quick phone call with a client on the street outside our apartment, 160.

“So when your girl is telling you ‘baby daddy make a baby with me i just want your baby’ and you’re getting off, remember this,” he projected a spreadsheet on the moveable wall. The itemized costs went code red—diapers, more diapers, formula (maybe!), food and more food, clothes, clothes, college. Then that sound again, 2 straight minutes of wailing.

The sound tugged my ovaries, hovering huge as the plastic drumsticks on the Thanksgiving Day Parade Turkey Float. I thought of my beautiful almost-husband, our unprofitable, flaming urgency, the pricey primigravida I might become. The leather conference chairs sighed under the shifting weight of adolescent pelvises.

Afterwards, my students went to lunch soberly, the cop grinning and high-fiving and making each of them say, as their exit ticket, which was the most expensive sound, now?

On my break, I called the sitter to check in on the kids. Her ringing phone was the sound of coins clinking in the gastrointestinal chamber of a porcelain pig.“They are doing great!” she said perkily, which is what they all say. “Great!” I said. “Great! I’ll be home by 6.” “Great”! So much greatness. The kids were almost old enough to not need a sitter. Almost.

Nonetheless, advice only takes us so far. At the ultra-corporate celebration for my students after their high school graduations, tables piled high with Panera bread and unidentifiable dips, cold cuts rolled in logs and glossy bagels, they mingled with their mentors and donors, their jumpy lives about to firework. Their hands jammed in their suit pockets, weight shifting from polished shoe to polished shoe, smiles as loaded as the buffet, they made jokes, still a bit too loudly, about what they were going to do with—to?— their girls, how far they were going to go. How good it was going to be.

That summer, 5 minutes after we married, my husband became my actual baby daddy. We watched the sun come up the next morning over the Catskill treeline, leafy branches poking at the ATM of the sky, from which light makes all of us wealthy, hoping our cellular investment, sperm freestyling for the deep end of the ovum, would soon yield cellular returns.

And indeed the ferocious baby grew inside me, with countless practice swallows and practice breaths to ensure he would perfect the most expensive sound in the world when his body was ready to make it.

When the bill arrived for my emergency cesarean birth, millions upon millions of pennies, I laughed. I put that invoice with its old friends, under the coupon for fencing equipment on the dining room table, where mail went to die. Subsequent invoices, I’d rip up, just for dramatic effect. You know what that sound is? The most inexpensive sound in the world! I kissed the new baby: “You know how much I love you?” I asked. “No, you don’t,” I answered for him. “Because it is not an amount!” In fact, some things evade quantification.

The flowering orchid, gifted to us to mark new parenthood, another overpriced thing we could marginally fail, seemed to blush a darker–browner?–magenta at such banter. Or maybe it was dying, lowering its regal head as the baby got better at lifting his. It was hard to figure out, in this life, if you were looking in the right place, for the right things.

Just then, my former student texted me: im near yr apt, w my mom. Can we meet yr baby? (“YES!”) I knew the baby, in those days pressed flush to my body like a man’s wallet to a back pants pocket, would prove to my student everything the cop had told them was true: yes, the baby would deliver the powerful cry that crashed banks, raised APR, and bounced checks. I knew I could count on him.

**

Did your birth or parenting story not unfold exactly like you were told it would? Did that first cry indebt you, too? Come tell your birth story your way, with us. January is pay what you can for sessions.

Newborn Eye Ointment & Other BS

When they asked us if we had applied the antibiotic eye ointment to the crystalline gaze of the newborn, we lied. Would you smear Elmer’s Glue on the Mona Lisa?

When they asked us if we had applied the antibiotic eye ointment to the crystalline gaze of the newborn, we lied. Would you smear Elmer’s Glue on the Mona Lisa?

“I think so?” My husband squinted convincingly at the baby’s soupy pupils, crass verification.

“There has just been so much ointment around,” I added. I spooned yesterday’s cold butter fish, which basically looked like melted ointment, into my mouth from a tupperware, trying to enhance the overall ointment-y feel in the postpartum bed, still smudged with my blood.

They came back 10 minutes later. The baby was still gazing at the atoms in the air. “Has the eye ointment been applied?”

“Definitely, likely,” I gestured in the directions of her eyes, each of them tracing a wandering star.

“We got it,” my husband reassured them, with the patriarchy’s absolute confidence in its own capabilities.

The nurse blinked at us intolerantly through her “I wasn’t born 1.5 hours ago” glasses. She held out the chart as if it were a valid form of life. Maybe even something that itself needed to be fed and burped. And appeased.

I kept voraciously putting butter fish into my mouth, the baby in my husband’s elbow, observing how hunger works from the middle distance. Yes, birth inundates you with a world of potential harms, but also with garlic sauce, hot showers, eyebrow stroking. The untouched ointment lay on the closest shelf, like a fresh catch minnow, stranded on a shore it couldn’t comprehend, a tube as bulging full as a Colgate commercial.

When my new daughter was first placed on my chest, I couldn’t unlock my face. No angels horned. The universe did not exhale. I was still arched, still wincing, and with some coaxing, collapsed back into the bed.

Holding her body ventral, I waited for the first angel to clear its throat. It was July, the hospital AC making the vents hum. The baby opened her mouth like an opera singer and the nipple waited there, still and stalwart like a school bus whose riders were being dismissed from the yard. “It’s right there, Close your mouth!” I whispered-commanded to her, “And give off that ointment vibe.”

She didn’t listen to either piece of advice, as parenting is full of sinkholes.

They came back. “She needs the ointment now. It’s not charted!”

In order not to go blind from a disease we, her parents, didn’t have, and so couldn’t have transmitted?

I raised my water bottle in a sordid toast. “Well, Let’s name her Chlamydia, then? Shall we? From the Ancient Greek, ‘Small Cloak?’” My husband nodded. We take names fucking seriously.

Her mouth was still open like a diva’s in the moment after her cadenza, before the grand theater is torn apart by violent applause. She wasn’t going to latch on my breast: she was going to sing to it forever. So she would be Aria.

In myths, the blind sing. The power of truth reverbs off the pure sense of their voice. The charts flap in the throaty wind, and all the bullshit scatters.

In the end, I did not give my informed refusal hard enough and they coated her eyes with the unnecessary antibiotic. “I am pretty sure the other nurse already applied it,” my husband tried one last time as they popped the cap. But the finger of the hospital was already upon her.

As soon as she was in my arms again, we wiped it off with her swaddle. Off fell her useless newborn hat. Enamored at life being life, we stared at her big, fishy stare. Her body felt like the verse of a song I had always known but never sang.

When we had our fill, she fell asleep with my husband’s upturned finger giving comforting pressure to the roof of her mouth. That tiny cathedral where the angels tuned their tiniest harps, where her reflexes tied us in a primordial knot.

This felt like the least of the lies we live on: that inside every moment, no matter the bullshit our conditioning and institutions try to coat us in, there is a nearly imperceptible 8th note of Completely OK.

Maybe Mona Lisa coated her own nipples, too, raw with pain for the child she’d never nurse. Maybe she’d take Elmer’s glue after all, if that was all they had to patch a wound, pushing a smile out through the fog, eyes on an indeterminate future where antibiotics both saved us and clouded our visions.

The goop had come and gone, and we were bare, fleetingly asleep. Is it more frightening for our children to see us clearly, or not to see us clearly? I’m not sure.

Ticking Time Bomb, Little Life

I was walking in Prospect Park with the 11 week old baby tied to me in the wrap, “helping” her sleep, which requires myself not sleep. Those two words always together, like Ernie & Bert: SLEEP + NOT. Anyway, if you sleep, life wooshes you by, right? You miss autumn’s golden filaments. Your rights to complain are nil, and other mothers hate you but pretend not to. The scariest thing is about to happen to me but right now the scariest thing is: will she sleep?

Sleep when the baby sleeps, they say with a chirp. Surely said by folks who drug their babies into long stretches of sleep, and then drug themselves into the same. Or how about shut the hell up when you’re not asked? That’s right, parenting advice column, I’m talking to you. And have you checked out the first gold filaments of autumn? No, that’s right, you haven’t. Too busy catching up on sleep. Nature’s not going to wait for you, honey.

Somewhere along the way, my brain switched to thinking about career writers, to a NYT’s review I’d read. Since, along with not sleeping, I was not sending out my writing, this seemed like a natural way to bash my self esteem. This particular writer’s character described her life as hurtling indifferently through space strapped to a ticking time bomb.

I felt that. Or maybe it was just a regular old breeze, with no message attached.

To keep things quaint, a couple of ducks screeched—hurtled— from the sky into the lake.

Hey, ducks! I said.

Well, because it’s a well known fact that ducks are anti-social assholes, they didn’t have the common decency to even quack back. Fine. I kept walking. A couple passed me, both heavily tattooed, both with eyes glued down to their respective phones—while on the most beautiful path in the park on the most beautiful day the autumn could come up with.

ASSHOLES, I thought, chock-full-a judgment. Look up!

Well, no sooner did I dish out advice, my nose nestled into the baby for a hit of that Baby Smell, when I felt one foot go out from under me, the ground rolled and threw me forward. I hit the path with my one hand out, the other trying to tuck the baby’s head somewhere completely safe, maybe back into my womb. About to know what it felt like to crush your own baby.

I felt myself bounce, roll, and then I was on my back, in a pile of the season’s first unglamorous dry brown leaves, looking up at the tree canopy, quiet rustle of leaves.

The tattooed couple (I LOVE YOU BOTH) came rushing back: oh my god oh my god oh my god, they spluttered. Even at that moment my judgment stood tall: HAVE YOU HEARD OF KEEPING CALM IN OTHER PEOPLE’S EMERGENCIES HO HUM IF YOU ARE LOOKING FOR A SECOND CAREER YOU GUYS SHOULD NOT BE EMT’s BUT ANYWAY.

Are you ok is the baby ok are you ok is the baby ok is she ok are you, you —baby—you—baby?

i guess if her head was smashed they wouldn’t ask, would they? Or would they?

I think so? I was not sure if I was speaking or thinking. The baby lifted her mighty head on her mighty neck from my chest and began to wail. So she was not dead. She was not bashed.

They knelt by my side, and I had a tour of their tattoos.

CAN WE HELP YOU?

Surely they were not yelling, but the ducks began to.

Yes, but SHHHHHHHHH.SHHHHHH. SLEEP WHEN THE BABY SLEEPS.

Because, of course, she had fallen asleep just before I fell.

They helped me sit up, nervously.

REALLY ARE YOU OK?

REALLY I AM NOT.

I checked the baby. I checked her like she was the last one boarding Noah’s arc, an audition before the flood. Body parts. Sound.

Her hair still stood up straight, as if she’d been electrocuted in a lightning storm.

I think I’m OK, I said. But if you can give me a minute, I think I’m in shock. If you could just stay with me a minute..

SURE SURE SURE, they said, reminding me of the nervous blabbering goose in Charlotte’s web.

It was the middle of the day, I could not have been more in love with them than I was with my husband when I agreed to marry him-- for being on that path at that moment, and for having the impulse to kneel and assist.

We sat up. I checked her again.

They pointed to the stick like it was the true ASSHOLE VILLAIN of this story. It was a very small but thick stick, the size of my pointer finger. No wonder I had not seen it. No wonder looking up is not always the best way to go through life.

I was pretty sure my ankle, which has been rolled approximately a million times in my almost four decades, was going to suck. But for now, it could hold my weight.

I’m going to walk, I told them, and was hoping for drum-rolls, angels clapping, a “NOT THE BIGGEST ASSHOLE, ASSHOLE” type award.

ARE YOU SURE DO YOU NEED TO GO SOMEWHERE? They rose with me and offered what they could, which was company. They picked the leaves out of my hair gingerly.

I wanted to let them continue on their tattooed way, so I could be alone with the fact that one of my biggest fears had just passed. I had fallen with her tied to me. I could have injured or killed the baby. I did not injure or kill the baby.

My mama stunt double had jumped in and taught me how to fall just so in an instant. And yet I knew she could have just have easily been busy elsewhere. I was glad I had not been on my phone, texting my husband something snarky or desperate. Then, my asshole status would have been confirmed. This was an innocent fall, holding my babe, smelling her, appreciating her ticking time bomb-ness, which some stick sought to detonate.

I thought of innocent people dying in innocent ways, surely long before they felt their work was done.

Sometimes all it takes is a stick, like in a zen master’s parable, to untangle you from the drama of yourself.

I walked very very slowly out through the park, checking every footfall, nursing my daughter on a bench along the way while guys in rasta gear smoked spliffs unapologetically across from me. I looked for signs she’d become demented or maimed that the filter of shock had not revealed. Was she missed a hand, some skin somewhere, was her jaw unhinged?

But she was just herself.

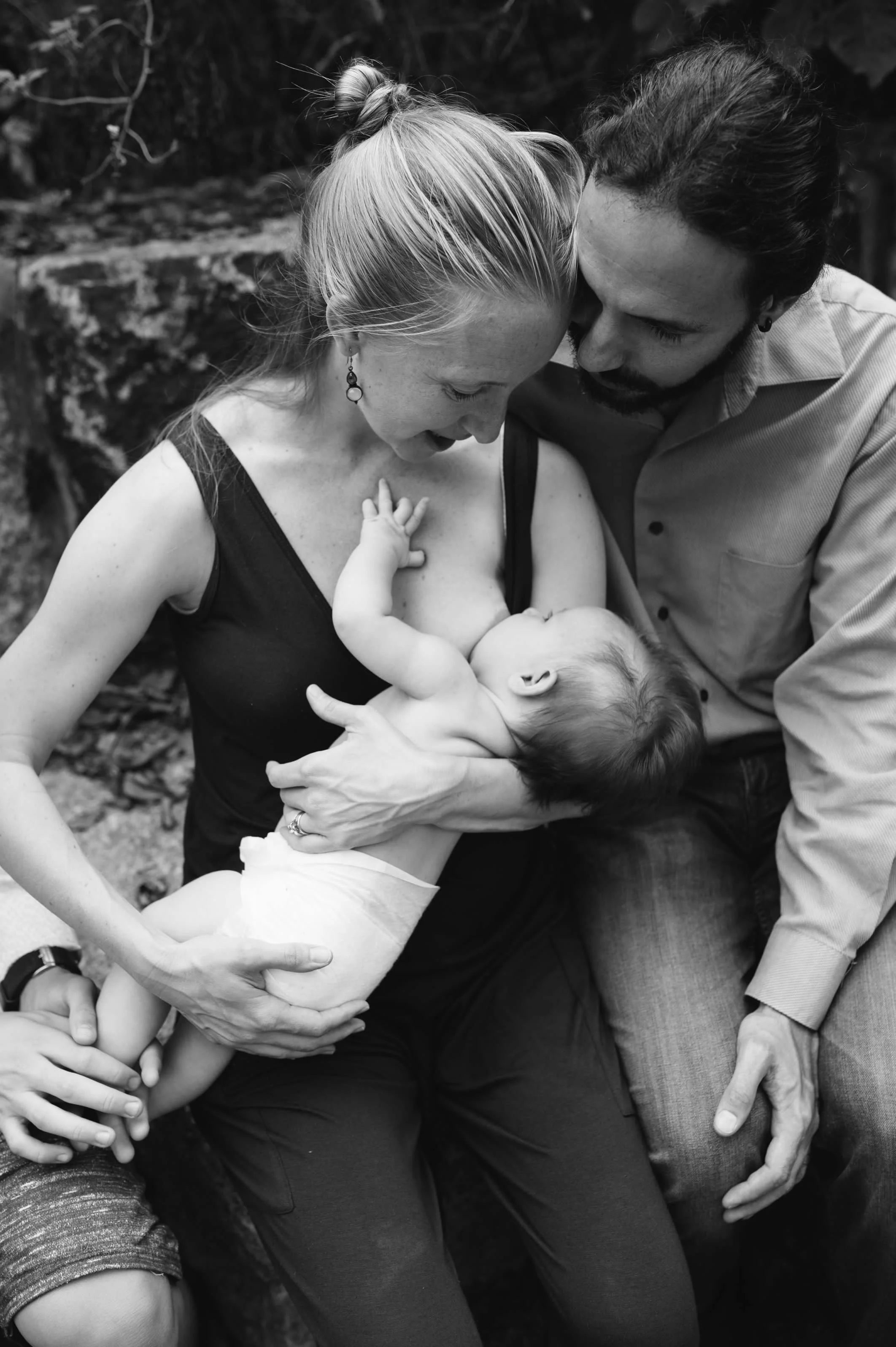

Nursing felt like the holiest thing since the nativity manger.

It is easy, when it happens, to respect how life changes, or can, in an ordinary, stick-in-the-path instant.

Of course, we don’t perceive that all our instants are like that: tiny capsules of mortality, which we are forced to swallow, until the one we gag on.

We can lurch to the ground anytime, causes obvious or not, warning signs obvious or not. There may or may not be passerby’s who can help us; the circumstances may be dignified, or they may be rather banal. My Tai Chi teacher in Thailand, for example, slipped ironically in the bath tub—chi doesn’t provide traction— and died of concussion. Her gentle hands did not brake her fall.

Sometimes, we fall down fatally in bathtubs. If that isn’t an asshole death what is? Only in literature might a death mirror a life in its poetic-ness. More often it’s a duck screeching into a bottomless dark lake.

Perhaps appreciating how slippery our lives really are should make my steps heavier, more decisive. NOPE. Lighter, tentative: can I commit to this if there are no guarantees? If fortune cookies are just, well, highly processed cookies?

I’ll be right here with my sneaker hovering, hormonal sweat trickling down my back, scanning the path for sticks with legs.

I had a baby; that’s what having a baby is: SLEEP, NOT. Once a pregnancy gets rolling, there’s a biological commitment to making a person, but how that person will be formed, its destiny, what will go right and wrong, is not up to me or you or the ducks or hills or trees or leaves.

When my daughter came out, she was examined and swaddled, but I’m pretty sure what they did back there, under the bland gaze of the pediatrician, was strap on the bomb, adjusting the buckles to suit her tiny form, and start it ticking.

Like the umbilical cord, these straps soon aren’t visible. But just as no person can (as of yet) come to be without having been tied to a placenta, no life can exist without premise of explosion, matter returning to matter, crumbling leaves to crumbling leaves, breathy trees to breathy trees.

When I get home with her, I sit on the couch, a little dumb. I drink some tea, and as my shock wears off, the ankle sets off sirens of pain. I can hardly put weight on it as I go back and forth on my domestic circuit, my son naked and yelling at me from the couch “I won’t listen to anything you say ever!” and my infant daughter, tripped by his asshole cortisol spouting, screams for an hour and a half straight. I yell at my son, no better for my scrape with mortality.

I call my sister, embarrassed, and confess to her that I am only calling her so I don’t keep yelling at him, while he launches himself off the couch over and over, knocking the paintings and photos sideways, like our lives. And the baby quivers from her own screaming, and I quiver from how exposed and exploded and present I feel.

Tomorrow we will walk that path again. I will apologize to my son, and explain. We will kick asshole sticks to the side, chipmunks darting, the weather temporarily just fine. I will be slower, hold her body even tighter, smell her head with one eye straining to see the ground. But there will still be that thing I will miss, the stumbling. The tattoo’d folks will pass, nothing to see here. But I’ll hear the ticking, barely masked by the soft sound the leaves make.

Artist Residency In MotherHood-- When Is Yours?

Artist Residency In Motherhood gave me not just time to write, but time to Be a Writer Mother or, as Cheryl Strayed encourages, to "Write Like A MotherFucker."

When I was invited by Stella Fiore, writer-mama and curator of the hit radio show Cut + Paste, to be part of an Artist's Residency in Motherhood (ARIM) this month, I said YES impulsively and before thinking through anything even vaguely like the Logistics. She was setting up a Facebook group (NOT ANOTHER FACEBOOK GROUP BUT YES) for that very purpose, and we could opt in if we wanted. Stella and I were colleagues pre-baby eons ago at as instructors at Sponsors in Education Opportunity. Our reconnection was random and fortuitous.

Her CUT + PASTE group differed from Every Other Facebook Group your Random Friend invited you to because of one thing I can hardly find the words for-- people showed up. Even the lurkers lurked well; but the moms who were posting were a brilliant balance of heartfelt ambitious and real(ist); fired up equally by dreams and delays on dreams. Each mom was participating in whatever way she could in an Artist's Residency--self-hosted, self-directed, self-sustained-- loosely scheduled over the weekend of Feb 2-5.

Lenka Clayton created this concept and inclusive shelter, Artist Residency in Motherhood, and I must say she is a MacArthur Level Genius. As an artist and newmother, she saw how art and motherhood are too often pitted as incompatible, inside oneself and by the world at large. Clayton decided to say a Fertile Fuckit, and make her art out of the materials of motherhood instead-- quite literally. Rather than see her two callings and practices as in conflict, she did brilliant recycling, for example: fished things out of her baby's mouth (when her baby was in that EVERYTHING ORAL stage) and used them to collage. Nap-length works, at the pace of a baby's fickle developing nervous system.

The deal is such: many mothers pull more than their weight around the home, and work damn hard for big and tiny bosses, for rough inner bosses, for the good of their families; and as kids come into our lives, it is harder and harder to justify time for ourselves-YOURSELF- to focus on your art. This is ESPECIALLY so if you are the (considerable) breadwinner (EVEN IF THE BREAD YOU WIN IS KINDA LIKE SHITTY OLD WHITE BREAD, IT IS STILL YOUR BREAD!) and EVEN IF your art is part (or, lucky lady, all) of how you win that bread.

It is something about prioritizing our needs --and to MAKE (ART) is a NEED-- that can rub us-- or is it the patriarchal culture?-- the wrong way.

Over the weekend, all kinds of moms did all kinds of things in all kinds of ways. We leaned into villages we didn't even know existed as such, or partners and friends who gave us time and spaces in which to write. Some of us had three hours to dedicate, some could take 36 or more. But behind whatever concrete time we had was the feeling and solidarity of all the moms-- and it was an international group-- doing Something that was theirs, that was from their making heart, that was about the Something Else we need to do in the world, even if it's intimately entwined in our mothering or parenting.

What did I do? Nothing, I hid out from the fam and read Samantha Irby and Lucy Grealy and ate dinner by myself in a bar where two men fawning over each other were exceptionally, teenagers-out-of-school-on-Friday type loud! Well, let me revise that: what I did was revise, and pour myself into something I knew would not be interrupted by anyone else's MASLOWISH TYRANNY.

My first goal was to have no goals-- because what good is a residency if it only leaves you disappointed in yourself? I wanted to revise personal essays, difficult ones, that had been sitting in my drafts too long-- but ones that aren't posted here because-- well, I want to publish them, and sometimes when you want to publish, outlets specify it can't have appeared EVEN ON YOUR GRANDMOTHER'S FRIEND'S UNCLE'S BLOG. These essays were about personhood and love and uncertainty (always) and my husband's challenging ex and my students who showed me a photo (or tried to) of a huge poop. They were, like life, about everything.

I meant to submit them; I didn't. But I got my pitches ready, and I got to saturate in the feeling that we were all doing something worthy and supporting each other, hard.

It's actually not hard to support each other.

My husband didn't clean while I was gone (boo) but he did say, "Everything was just so easy with the toddler!" Proof that 1. I should go away more because it's good for the toddler's grasp of etiquette and 2. Family doesn't cave in if a pillar goes for restoration.

And, finally: My old friend insomnia came to visit during the night. She is an orgy gal and rarely hangs with me when I am alone these days (because I never am?) but there she was. So I got to read books in the middle of the night, and do yoga nidra, which I highly suggest for you when INSOM comes to call.

Essay Experiment #18: Peacock Procreation

Just as the male peacock is about to have its way with the female, feathers spread in an alluring fan, exposing extra layers of tail pompadour, rattling and shaking and calling in a pre-hump display of color, texture and sound, my toddler runs up to it.

Just as the male peacock is about to have its way with the female, feathers spread in an alluring fan, exposing extra layers of tail pompadour, rattling and shaking and calling in a pre-hump display of color, texture and sound, my toddler runs up to it.

PEACOCK! He yells. PEEEEEEEEEEEACOCK!

You know, if someone ran up to you and yelled HUMAN HUMAAAAAAAAAAN! HUMANNNNNCOCK! just before you hit the roof with an orgasm, you might pull back too-- just saying. And toddlers know these things intuitively, the way they know crackers and fruit are good and everything else is not.

Understandably, the male honks away, annoyed, at best, blue-balled at worst, not gonna propagate at worst worst. Its glorious fan of feathers collapses and drags on the asphalt behind it.

We stand on the curb of a lawn in San Antonio suburbs, at the cul de sac on Dusquesne street, rolypoly bugs and mosquitoes prowling, and watch the marvel of domesticated peafowl trying to get it on. Animal behaviorists call this place a "lek", where males assemble and engage in competitive displays to attract females. It's mid April, the dizzying season for baby-making.

My husband reaches out and pinches my butt gently, so the children cannot see.

The toddler startles a few males into retreat, moments before their sperm can begin its spasm-assisted journey up the cloaca into the uterus of the peahen. He explores a parked car with a busted tire and dented fender with the same untempered interest, running his palms along its hub like my stepson ran his along my back during labor. "CAR!" Ro yells, ruining its chances of scoring with the lady cars; "CARRRRRRRRRRR." and "It's hurt?" He points to the dangling fender bit. It does look sad and hurt.

He pat-pats the greasy deflated wheel, tries to wrench the fender back, because toddlers know that everything feels intensely, intuitively, the same way they know intuitively that laundry is for dumping on the floor.

When Ro senses in our shared bed that we want to "snuggle," he wields his complete sentences: "Daddy, don't hug Mommy! No, Mommy, go over there!" He doesn't know exactly why this is funny to us but he'll physically remove my husbands' hands from my body, because toddlers know intuitively that their parents' procreation would disrupt their social order, which is to say their ability to be the only one who gives orders and because: boobs are theirs.

The male peacocks fan and flutter and ruffle and flutter and pitter patter. And the females--peahens, much drabber in color and more self-possessed- peck with disinterest at the lawns, eating who knows what little critter. It's fun to watch the males try so damn hard, and the females be so unflinchingly picky, hard to please. It's actually inspiring.

I remove my husband's hands and pretend to look at the bugs. I haven't seen roly-poly bugs since my childhood, when they were common in our backyard, easily frightened into little balls.

I cannot imagine the peacocks tritely agreeing-- in their unnerving mating cry to accept this human behavior-- toddlers will be toddlers! This too is one of the way life manifests itself: toddlers capsize sex and insert themselves like punctuation marks--and species fail to commiserate.

Such Interruption is the story of our lives.

And by "our" I mean my husband and mine.

And the rest of humanity who somehow got through the toddler stage with their hinges intact.

In this neighborhood, peacocks roam free, loose and ubiquitous, not an anomaly, not a majesty, in the conjoined front yards of Texas Suburbia and up and down their concrete driveways. Suburbia has a shocking, refreshing amount of green; it soothes my too-much-on-the-computer-too-much-urban-life eyes.

Here, peacocks are neither pet nor pestilence; they are their own thing, glorious in juxtaposition with suburbia's main feature of being unremarkable. They move through the property lines, honking, flapping, strutting, and pooping.

We are roaming streets to find the peacocks being peacocks with the children, my husband pushing against the weight of nostalgia. These are the streets he grew up on, playing ball, the moss in the heavy trees, this one neighbor--can you see her?--who was so uptight she didn't want kids touching her lawn. If your ball happened to roll there, you had to be fast, but she was faster, waiting at the window for a transgression.

Peacocks appear in paintings, in kingdoms. Their long feathers are strewn across the lawn, catching the light, defiled exotic. Royalty would never visit here; they have sent their fowl ambassadors and because they were fed-- grains-- they stayed.

We are fed; we stay, too.

Texas in Spring is forgiving, while Texas in the summer makes outside unbearable. The birds too seem to know they are in a period of pleasantness, and in their biology they prepare for the future by creating those who will populate it.

It hasn't hit 80 degrees--yet-- as the mosquitoes hoped it would, sweat making every living thing more scrumptious. It rained too much in the past two weeks, and so the grass is an excruciating green.

Our minds still filed down from long days of plane travel, we pack into the rental car and drive through Hill Country to see my husband's old dear high school friend, who has had some hard times.

Down the road from her dark house are two horses at pasture, white and brown. A sturdy white fence marks the perimeter of the field. The land is dusted in fuschia and yellow flowers, like a jigsaw puzzle that would make you crazy, especially once you realized your kids had lost the final pieces.

LeAnn leans against the fence, her hair in a tight blond bun, fiddling with her fingers and looking out at nothing much. She tells me not too quietly that my husband's ex was always jealous of her, just because she and John were longtime friends. I'm incredulous but she can't say much more about it, because my stepsons are right there, scaling the fence, doing parkour in the grass-filled ditch on the side of the road.

The toddler tries to copy them, then begs to go through the slats of the fence and see the HORSIES. Toddlers don't understand fences. Horses have a better sense of them.

The peacocks have no fences, but they seem to contain themselves within certain areas of the neighborhood, only occasionally and idiotically getting run over by a car. My mother-in-law's second husband, R, tells me that one peacock was hit by a doctor, speeding through to get to his shift at the hospital. The doctor was remorseless, the huge bird lying with a track mark through its fat breast in the road. Residents yelled from their homes, and the doctor said something to the effect of, stupid birds, I have to get to work to take care of all you assholes.

Mmmm, the ethos of healing.

LeAnn's house, like its owner, is too depressed, and after everyone has had nutella and peanut butter and sugar and sugar and sugar sandwiches, we set out again, down to a lakefront where you can swim if you want to be slimed and cold. The geese on the shoreline honk in their pissed off way, waiting for whatever visitor will give them more fresh-ripped pieces of stale whitebread. I can feel them feeling our dietary idiocy and loving it. Their sex is undainty.

The trees look like something Dr Seuss would draw, but on a morning he woke up slightly and inexplicable aesthetically inclined to be a realist. The grass is as long as my son's hair. Everything feels jacked up and totally alive, photoshopped into a perfection just by looking, past made vestigial by the flip of sky reflected in the incandescent water. We are sandwiched here between earth and heaven, and that is the whole thing.

My son narrates his own movements and everylittlething he sees, and attempts hazardly to climb a playground set.

He has me chasing him through plastic tunnels, bright red and blue, that the light of the sun shines through. He make intermittent, predictable announcements about his own whereabouts, like a conductor announcing train stops, just in case you weren't paying attention: I am in here, I am back, mama don't come in with roro, I am in the plane!

Hands and knees, crawling after him, waiting, listening to him.

Listening.

He imitates the peacock's cry, calling. I keep expecting a peacock, from miles away, to yank up her picky head, turn her eyes to him, melt.

We are, essentially, killing time at the playground, waiting to end this visit and drive to another, conversation slimming down to nothing, down to just sitting and standing around together and that being enough because: the past. Because: the present. All day in a kind of neither pleasant or unpleasant stasis, I keep thinking, this is it, this is all there is.

This is it this is all there is this is it and yet we keep going.

A moment of stillness from a silent meditation retreat of a decade earlier slides back into my bones like an egg resting in the bottom of a freshly dug nesting hole.

It is like getting the realization without the cost of the meditation retreat. Or you could say that your whole life is the cost of the realization.

When we are back in San Antonio, we walk again. This time, it's apparent mating has already begun in earnest, and with results. The Peacocks have dug holes and laid their fat eggs in the lawns. The exotic meets the cliche. The eggs are not well hidden and many nests stay unprotected, hardly sat on. You would think it would take more work and discretion to make something as complicated, spectacular and bizarre as a peacock.

By contrast, our human mothers volunteer their very lives to be sure we come to developmental fruition--you want her, you will have to take me, our gestation method announces, even if the mother privately feels anything but. We protect you wee things with our whole existence.

But my toddler runs after his abler big brothers, then climbs a bank of dirt and ivies and plunges his hand into the nest full of eggs. His Grammie assures us this one has been abandoned, but I am not as confident why. He holds the egg up high enough to break it if he drops it, which he is wont to do just to check if, you know, gravity is still a thing and what his special powers are.

I feel worried for the incipient peafowl, though my husband can tell by holding a light to the egg that nothing is growing there, there is no vasculation, no ghostly yolk becoming a discernible embryonic particular.

Put it down, I say with too much worry in my voice. Already giving the toddler too much power. He flashes me the creepy grin of knowing he can do something he should not. He's already stepped on hundreds of innocent rolypoly bugs, stomp stomp killing for no reason-- Gentle, I say. This is like the egg Fossey came from.

Fossey is our hand-reared baby parrot. I met Fossey right after birth when we heard a peeppeep and a grisly creature with no neck control wobbling in the nesting scraps. Sooner after birth than I met my own son. My husband and I peering into the nest box and starting to cry simultaneously, which is something that just happens to people-- even assholes, as one doctor told us-- when they witness the beginning of life.

The peacocks honk and wail-- but for sex, not protection. Begging for it, some might say. Like Fossey, I remind my toddler again, thinking the personal connection will be enough to stay his throwing arm. He wouldn't hurt that, would he? He grins again, but I can tell the analogy didn't hit home with the moral harness I'd intended. Egg! He says, and holds it up even higher on his tippy toes, peacocks fornicating on the cul-de-sac all around him. The power of man, I think. To hold on to someone's fate at every moment, to unthinkingly let go.

Experiment in Essay #17: Starring, Pants--#52essays2017

I am making a movie about tantrums. It is going to star my 23 month-old son. He is handy and doesn't need to be paid and knows a thing or two about the subject. I have a day job--most days, it is called getting through the day-- but I feel fairly confident we can shoot footage even in the middle of the night if we need to. Such is the convenience of living with a star.

I am making a movie about tantrums. It is going to star my 23 month-old son. He is handy and doesn't need to be paid and knows a thing or two about the subject. I have a day job--most days, it is called getting through the day-- but I feel fairly confident we can shoot footage even in the middle of the night if we need to. Such is the convenience of living with a star.

His verbal ability is rocketing. He says things like NO I DON'T WANT TO PUT ON MY PANTS MKAY?

He repeats it as you approach with the sad sack of pants with all the benign respectful leadershippy approaches you learned from podcasts on graceful parenting, damnit, with the vague and vain hope someone would some day write an article on you. You're that good at this crap.

Pants? I DONT WANT PANTS, he reminds you in case sentences die on impact. MKAY? I NEED MILK. DONT PANTS!

And he still yells just to make sure you have understood.

Writer's interlude, in which she pretends she can still think critically: If google is so advanced why didn't its spellcheck guess that I was missing an apostrophe in the contraction above, when I spelled "don't" like it sounds-- DONT? Autocorrect suggested WONT and FONT. As in: No, I WONT want to do what you want--no matter your fucking clever essay FONT.

I, the mother, am suggestive under the influence of tantshrooms. I start saying things, nonsense things. I am no better than the toddler. If such clothing anarchy doesn't bring out the worst in you, take me out for drinks and tell me how. I will put you in the film credits, near the end.

Brute force is not my thing. Forcing someone to put on their pants feels like inverse violation. Don't we teach kids no means no? But we don't like it when they use that against us. "I threwed it!" The 23 month old star says about his shirt, gloating, but also about my equilibrium. My equilibrium is the opposite of pants, look at them, the right leg and left leg perfect reflections of each other, such admirable balance. Who could hate them, with what cause? Isn't that like hating puppies, baby giraffes?

In the grips of TanTrum, in the dark main street of TanTrum Town, things are bleak. Clouds roll in and make the light for our shoot crappy, but we don't care, because we have star power. My toddler leans back in his high chair nude as the day he was born which was not that long ago in relative time. He is ready to play his part so well you would never know it took his whole life of training to arrive at such a convincing show.

So, check it, critics: Today sucks the most but tomorrow could suck even more which is why we need to get the documentation on so we can remember how good we had it before things tanked. Also, mamaguilt sets in as I try to squeeze satire out of my own sad attempts at dressing him: after all this using him for material-- what if Ro has ACTUAL sensory issues? Not so much that he likes being in his diaper as that he hates the feeling of everything else? And then I would feel awful for not commiserating more, for getting into a battle of wills rather than being a paragon of empathy. I would be the accidental villain, part of the job description of parenting, the part they put in small print and hope you don't read until your contract is signed.

Brute force is not my thing but I am kinda thinking I might need to black market purchase a hospital smock and go hide out in the postpartum recovery welcometotheshitshowofmaternity ward...and watch the shaking baby video.

Or maybe wherever you birthed should invite you by 20 months postpartum to a special screening of Shaking Toddlers. Or mail you cartons and cartons of box wine and a note: "Not everything improves with age!"

So I tell my brilliant agreeable son--because I still speak to him like he is capable of apprehending reasonable speech-- he will have to star in this video we are going to make together about tantrums, huge tantrums, and that when I put on his clothes he should go apeshit and yell. He has been doing this all morning anyway to new levels of intensity and has it down pat.

Writer's interlude (because you guessed, didn't you, that I had to have escaped into the real world to write this all down? You know that can't happen when I am rescuing pants all day, right?): Look, Look around for proof that life goes on, and will even after our movie is made; on my subway, there is some guy, dressed in tight blue jeans and a seablue synthetic sports shirt, trying so hard to give away the empty seat on the train to a woman before he occupies it. "M'am would you like to sit?" He asks me, with incredible self-satisfaction. When I at first don't realize he is talking to me, he repeats it: JUST LIKE his mama taught him. I shake my head, and wonder if I look pregnant or ill. In New York, little else propels Random Acts of Politeness. But then he asks another woman the same thing, and another, with a pained pinched "This is how I was brought up!" Smile on his face. I wonder at what age he started putting his pants on himself with no fuss or if he still, in the privacy of his home, cries hysterically to no one while he sticks his foot into his jeans.

I coach Ro while I change his diaper, which also offends his sensibilities-- and I pull it off surprisingly without summary execution by his foot into my throat. "OK I am going to pick a pair of pants and when I do you need to go buckwild, yelling and protesting and doing the worm and stiff as a board and crying!" Maybe I am getting carried away but he says mmmhmmm, like he is a Jew fleeing the plagues with Moses giving instructions, the first plague is Outfits, towering over the Earth.

I continue, conspiratorial, egging on the overblown drama of our little lives: "And then your shirt, okay? Do not let mama put that shirt on whatever you do. Yell, scream, howl, bitch, make sure the neighbors think I am sacrificing your testicles, OK? You have to do it like you really mean it and do not back down. If I get the shirt over your head and colossal green protruding noseboogers, do NOT LET me win, pull it in the opposite direction as hard as you can! OK, ready?"

We are both super into it. Parenting is amazing.

I run into the livingroom for the surprise clothes move-- trust me, every other more enlightened approach hasn't worked for shit-- and whisk him into my lap and the pants and the shirt and ---

He is mute and cooperative and holds out one legs tentatively but amiably.

My movie is a flop, but my life a riveting, riveting success.

Experiment in the Essay #14: Just Almost

These days, I feel like the queen of almost: almost got the job, almost missed the train, almost burnt the toast. A palm-reader would frown at my life-lines and declare: "Almost!" But Justin isn't talking to me, in particular. He is talking to the camera, his buff-ness redoubled in an off-screen mirror. What he says doesn't have to be true, it just has to sound convincing.

"Just a few more, you're almost through," the trainer encourages, two reps into the set.

These days, I feel like the queen of almost: almost got the job, almost missed the train, almost burnt the toast. A palm-reader would frown at my life-lines and declare: "Almost!" But Justin isn't talking to me, in particular. He is talking to the camera, his buff-ness redoubled in an off-screen mirror. What he says doesn't have to be true, it just has to sound convincing. The way muscles convince us of strength despite invisible vulnerabilities.

"Almost there!" he repeats, like "almost" is a scarf of indefinite length being pulled from a clown's throat. And if you're wondering, you're the clown.

And: No, we're not almost through. Personal training is all about accepting motivational lies, and using them as a reason to carry on in the face of something hard.

Anyway, this is not personal: he's leading a workout video on youtube. He doesn't even know I exist. He doesn't know if I'm exercising along with him, or just watching him perform, standing there in the living room, surrounded by toy cars and scattered Legos and a balled up diaper, in my billowy lace nightgown, picking my toes.

Which I'm not, I'm trying to keep up--and I don't and never will own a billowy lace nightgown-- but still. "Just a couple more, we're almost there, c'mon, sweethearts!"

What? No, we've just done three reps. Three out of maybe twenty? We're not almost anywhere.

The trainer has comically sculpted arms, and a delicate mustache, which looks like an accident he then made the best out of. And while he's clearly bench-pressed his arms until they are as unmissable as a cathedral dome, he's plucked his mustache with converse intentions, until it's as subtle as floss in a mound of newly fleeced wool.

Being hugged by him would be like getting hugged by a trash compactor: too much muscle, not enough tender places. But he's not going to hug you; he's going to work you, so c'mon.

I chose this video because it is low impact, which my inflammation-prone feet require. It's got a brand name to indicate: LIT. The shorthand promise is that Justin- that's his name, and no, I didn't make that up for literary resonance with my essay title, m'kay? -- will light you up. He's got two slender women behind him, doing the workout, just to prove it.

They glow. Beads of sweat make them look like Rockefeller Christmas Trees.

He calls them, singly and collectively, "Sweet Heart."

Dani, stage right, does MODIFICATIONS--you know, the not that hard stuff, NO SHAME IN THAT-- because, he explains, she "just" had a baby.

What? Just had a what?

Now "just" is an unfortunately casual, highly overused, too-many-reps-per-speech-act temporal adverb. It really means nothing, because it means too many things, and like beauty, the time scale intended/signified by "just" is in the eye of the beholder.

For example, 23 months later, I also sometimes feel-- but don't always any longer say-- that I "just" had a baby. My stomach has repaired itself by a lot, but the extra skin and ropy scar tell another story of pregnancy that doesn't end with labor. Mostly, things are in tact down there. I stopped doing postpartum-specific workouts only a few months ago, and almost by accident did the word leave me behind. My identity loosened as my abdomen tightened.

But hold on there; if Dani "just" had a baby, like, literally, why the hell is she doing this workout at all? With her imaginary hand weights and sweat-slicked face, slightly reduced range of motion. I can see the new moms cringe at her, or even, god help us, try a few of the modified moves themselves, baby in a football hold in one arm, or draped over the shoulder puking on a cloth-- that baby, the permanent hand weight, skewing the neckline, fatiguing the trapezius.

Even minor exertion makes tissue we didn't even know we had throb, like an ice cream headache in the uterus.

Most new moms lose any concrete, objective sense of time and duration, desperate too soon for their body "back" (that doesn't happen, not in the way we think we mean- some things change you permanently) or their old routines, a familiar self, or to do reps like Dani-- no, no way, she did not "just" have a baby.

But also, we're not "just" doing a few more until the set's done; the set has just begun.

So what is this, the rush to have (hard) things be over, before they've hardly gotten going?

And what is this other thing, how we redefine ourselves in the wake of transformative events (say, a death or, say, labor-- or God's labor, whereby we get the grand calendar markings of AD and BC), and count time from there, in quantum?

By this logic I am still new to the universe; because, you see, I "just" got born, 37 years ago.

Give me all the ab-strengtheners you want, trash-compactor, Justin. There is some damage you can do nothing about. There is still a larger hole in the tissue behind my belly button. I can palpate it, sink fingers into it. It's where the micro-tears on the transverse abdominus amounted to the muscular separation that precedes postnatal separation. Diastasis recti.

You can correct the condition, of course, with consistent targeted exercise. The exercises are subtle and repetitive, ad nauseam, like blinking if you squeezed where the lashes touched, every time. Eventually your eyelids would become very, very strong-- but you'd lose your mind in the process.

The thing is, no real workout is autonomic, and it shouldn't be. Except, you might say, what the heart "just" does without our consent, without a training plan, daily.

9 months pregnant, I would sometimes joke with my husband that maybe my baby would take the easier route out, skip the vagina altogether, and pop through my umbilicus like a chip-n-dale dancer from a white frosted cake. It seemed like there was sufficient diameter in the torn muscle for a head to fit.

In the end, that's sorta what happened.

Back to Just Almost Justin.

And what is this, these lies about recovery that make postpartum women damage themselves, judge themselves, rue their new condition? It's true that a few Amazon tribal woman could-- or must-- handle a workout a few days after child-birth. But it's not the norm.

It "just" what we expect from ourselves, to always look as if nothing has happened to us. God forbid someone can tell birth took effort. God forbid if someone can tell waking up in the morning, pouring the tea, turning on the lights, took effort. And then, of course, we must feign that negotiating with our minds is no effort at all. The seamless sweaty package of our lives is easily lifted.

I want to pull Dani out of the video and give her savory lamb stew, chunks of parsnip, water and green vegetables sauteed in pasture-raised cow butter. But instead I work out with her, wondering. Where are her leaky breasts? Why aren't you knighting her with a gold medal for getting through two reps? Why is there no baby nearby, who might need to nurse? Why is she in form-fitting sexy clothes?

Many of us live starting each thing only to be done with it. And perhaps a workout is meant to echo this-- push yourself, it's almost over.

It's not almost over. Or maybe it is. Depends how you view time. Einstein apparently said that time is not an arrow at all, contrary to pedestrian belief, contrary to the industry that sells you new calendars every year, daily planners. But I learned from a physicist that, actually, Einstein asserted his revised theory of time only after the loss of his beloved, and facing his own death, trying to make sense of his grief and pending destruction of self. If time is not an arrow, then death does not always have the ace.

So Einstein was hoping for a loop, for personal reasons, he did not want this to be the last rep. He wrote elaborate equations to chart a different kind of progression. But in the end, he died.

The post-partum woman is in possession of the most delicate arrow nature ever suggested. She must go through major postural adjustments to hold this creature effectively to the breast, or properly offer a bottle. She positions this creature towards the future, and with her whole body, she shoots.

Justin's arms glisten with new sweat, he keeps sweating, he's working out right with you. Or maybe he's been rubbed down with vaseline, shiny and clotting his pores. In personal training, sweat is testimony. Sweat is evidence that either THIS THING WORKS --OR you are in terrible shape or hormonally driven metabolic flux, m'kay?

Stop picking your toes. Tie your nightgown up in knot so you don't trip. Fake like you changed your socks this week.

Look at Justin's arms-- don't they inspire you to do that final push-up?

The camera zooms in, but we know why, his biceps are meant to keep you just a tad jealous. We live in a culture of Biceps, as a synonym for accomplishment, discipline, pushing yourself to the end.

Women, gather near. Justin will be happy to give you a workout tailored for the sweetheart you know you have somewhere inside you. The one who's not pissed about the dishes being dirty, about the crap all over the apartment, about the number of times we forget the rice in the cooker and have to throw it out, but not until you again google, "How long can you keep cooked rice in the rice-cooker?" and read through the string of contradictory answers.

No, you are just a sweetie with a body, and you are almost there.

Justin's full attention is on your low-impact needs.

Have you ever seen a woman's face when she's pushing a baby out? It's purple-red sweatasfreshplum. It's eyespoppingjawclenching. It's too many words too close together. I never got to push, I never got coached to press the plum through the veil of my body. Just when I felt that urge-- and they say you'll "Just know"-- the ambulance pulled up I leaned against the door of the building trash chute, heavily coated in thick, jet black paint. The paint glistened, feigned freshness. This is how something old stays looking new.

I was burning fat, all right; burning right through each fat motivational lie meant to make you think you can forge the impossible and move a baby through objecting bones, using muscles you're only partially in charge of. In the face of this repetition, well-meaning people say things like, "Just breathe," or "Just one more” and “you’re almost there!” When what they really mean is that there are few things to say that actually help, so they are just picking one, because they have to say something. An almost truth. Just for now. One small lie to move the needle. And then just one more.

--

Etymology:

just (adv.) "merely, barely," 1660s, from Middle English sense of "exactly, precisely, punctually" (c. 1400), from just (adj.), and paralleling the adverbial use of French juste. Just now "a short time ago" is from 1680s. For sense decay, compare anon, soon. Just-so story first attested 1902 in Kipling, from the expression just so "exactly that, in that very way" (1751).

And this infographic:

https://www.myenglishteacher.eu/question/how-to-use-just-can-you-explain-the-meaning-of-this-adverb/

--

Essay Experiment #15: Monopoly Problems--#52essays2017

So, spoiler alert: Yup, Monopoly is just as boring as I remember.

Let's talk about monopoly.

Wait, don't leave.

It is not as boring as you fear.

It's (even) more boring, more, more, more.

But so is breathing, right? And few quit that earlier than they have to.

Hey, anyway, the board is already set up. Clean piles of money. And you? You are a good parent, invested in the interests of your children. They don't want to read your books on dark money or addiction memoirs that end in water or breastfeeding either, m'kay? They find those tedious. And so you find yourself on the floor, shins crossed, wishing the game would vanish inexplicably.

Monopoly.

The plot and purpose and structure are: You go around and around in circles and buy shit and hope people land on your property so you can charge them for shit.

I have never on purpose wanted to have something so someone else couldn't have it, but I may have done so accidentally because: whiteness.

I wonder if Monopoly is a white person's game.

So let's start like this. After 5 hours on a Saturday morning with my toddler and my 10 year-old (while my 12 year-old was off at a gaming store in midtown Manhattan, exploring his new freedom to be only with peers in someone else's monopoly, and his ad hoc social life) my toddler fell asleep. This only happens if you try to put his pants on to go outside, he has a fit and falls asleep because: pants.

He basically has clothing narcolepsy.

So facing an aborted trip to the park and with a bright hour to myself to write ohmygodmygodohmygod I vie for sainthood and instead ask my 10 year old if he wants to play a game.

Now, he is fun to play games with and my stepsons have a towering pile of real games in their rooms that don't get played with enough, games with pieces that you could for example lose because: don't give enough of a shit about stuff. He has strategy and is just growing out of changing the rules when he's losing, a phase I am glad to be almost maybe next week done with.

However, what does he come back with? Connect 4 and Monopoly. Connect 4 is the back up plan. I love Connect 4. But, alas. Monopoly is the plan. And I must be vying for Sainthood because I said OK great let's play as I felt giant tears of boredom trickle from the armpit of my soul, if you will.

Now before you canonize me, please know that because my baby only takes long naps when, say, I have to be somewhere important and have no help, I knew there was no way this game would last more than an hour and a half because he would wake up and throw pieces everywhere and rub the money around and done.

Sorry, toddler tornados everywhere destroy valuable wastes of time.

So, spoiler alert: Yup, Monopoly is just as boring as I remember.

You basically go in circles and buy stuff until you go bankrupt and then you keep buying stuff because this is America. You gotta keep up with the Joneses and the Rodriguez's and the Trumps. Did I say that? And the system has all kinds of ways to help you go into debt because: capitalism and economic oppression.

Aren't credit cards a miracle of geometry? So thin you could pick a lock with them, yet so thick with narrative. The foundation for a tower of loss from which you can grow and grow your hair but will never get out without a collection agency stabbing you in the back. Rumple-monthly-statements-kin, or some such mythical creature that hounds and hounds.

Then you have to hope people roll the dice and land on your shit because if they lose you win hence capitalism hence whiteness and hence: acquisition.

You buy shit you don't want and maybe can't afford and definitely don't need--just so someone else can't have it.

You spend time thinking how you can get that golden 500 bill out of the bank without anyone seeing.

The banker, if you're playing with kids, has to be Not You. Your opponent who is forgetful pretends to forget what denomination bill you gave him and gives you wrong change, too little. They call this cheating but let's be real, the real bank is always taking more than its share. Cheating is contagious. Every time you stroke an ATM, a bit of that value is spat into the culture with your withdrawal.